Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Theological Reflection

themes of piety, virtue, trauma, courage, and grace in one of the medieval era's greatest poems

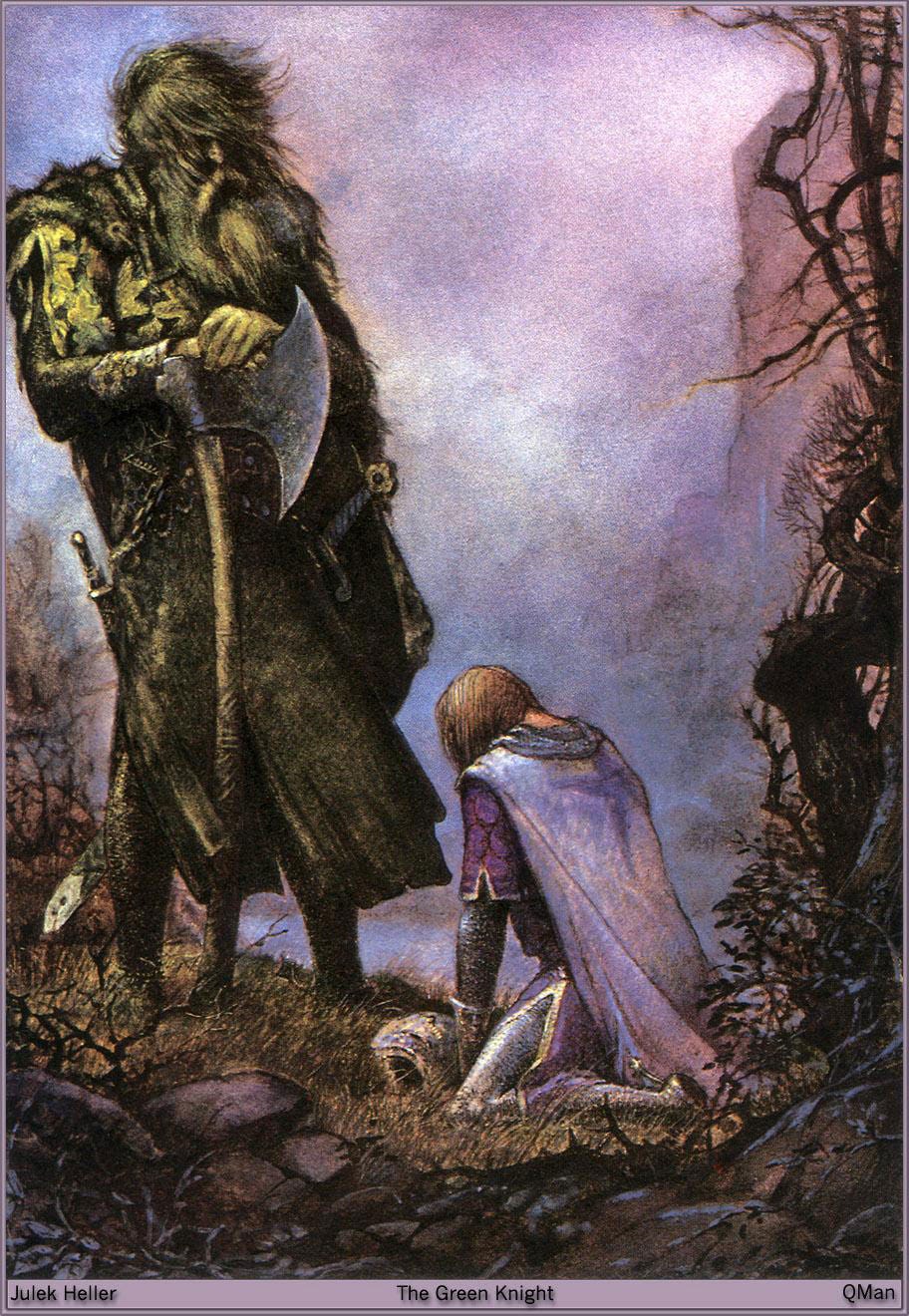

My Christmas book this year was the epic poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. It is a medieval English poem written by an anonymous author, though many suspect it is the same author as the other famous poem Pearl. The narrative unfolds in the Arthurian court of Camelot during a New Year's celebration (which, liturgically, is one of the feast days for the 12 days of Christmas) when a mysterious, gigantic Green Knight appears. He challenges the knights to a game: he will endure one blow from a weapon of their choice, and in a year's time, they must seek him out to receive the same blow in return. Sir Gawain, King Arthur's nephew, accepts the challenge in order to preserve the honor of King Arthur because no other knights will volunteer for the challenge. Gawain then beheads the Green Knight. However, to his surprise, the Green Knight picks up his own head and says, “I’ll see you in one years time.”

The story follows Gawain's journey to fulfill his part of the bargain, facing various trials and moral dilemmas along the way. Gawain encounters the enigmatic Lady Bertilak, who tests his virtue, and he ultimately faces the Green Knight in a confrontation that exposes the complexities of chivalry and human nature. The poem explores themes of honor, temptation, and the nature of true courage, offering a mosaic of what one might call ‘medieval-gothic’ with impressive moral undertones.

The plot itself is riveting, but description alone does not do justice to just how brilliantly the prose is composed. For example, here is the opening passage:

Since the siege and the assault was ceased at Troy,

The city demolished and burnt to embers and ashes,

The hero by whom the plots of treason were wrought

Was tried for his treachery, the truest on earth.

It was Aeneas the warrior and his noble peers,

That since conquered provinces, and became patrons

Of almost all the wealth in the lands of the west.

The alliteration and rhythm are astounding, and they give the poem an exciting pacing throughout. But in addition to the prose, I found the themes of the narrative quite captivating. The main themes revolve around virtue and morality—namely, what it means to hold fast to one’s virtues when they are tested, how faith and courage live out in fear, and what it means for imperfection to be redeemed and integrated into something more beautiful.

[Spoiler warning: Ending of the Tale]

At the end of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Gawain keeps a gift from Lady Bertilak—a magic green sash of protection—instead of giving it to Lord Bertilak as they had agreed. Gawain confronts the Green Knight at the Green Chapel to fulfill his part in the beheading game. The Green Knight feints twice before delivering a superficial cut on Gawain's neck, revealing that the challenge was a test orchestrated by Morgan le Fay (the evil witch in Arthurian lore) to examine the virtue of Arthur's knights. Gawain's acceptance of the green girdle as a protective charm is exposed as a failure to fully adhere to the chivalric code. Gawain confesses to King Arthur and the court everything about his journey—including his moral failure. Although ashamed, Gawain learns the importance of humility and the complexity of human imperfection. But more importantly, he learns grace because, rather than shame him, King Arthur and his court forgive and celebrate him. Gawain continues to wear the girdle as a symbol of his moral frailty, but Arthur’s court instead adopts it as a mark of honor.

There are many valid ways to interpret the story, and I don’t claim to have the definitive reading. But what follows are some of my own theological reflections on the story.

Piety and Theurgy

In the narrative, Sir Gawain is a man of upstanding virtue and chivalry. This is captured by the symbol of the “pentangle” upon his shield. The pentangle is a five-pointed star (think of a pentagram), and each point represents a virtue that Gawain aspires to uphold:

Friendship: Gawain values camaraderie and strives to maintain strong bonds with his fellow knights.

Generosity: He is committed to generosity and open-handedness, reflecting the ideal of a noble and selfless knight.

Chastity: He is devout in maintaining purity, striving to avoid both physical and moral impurities.

Courtesy: He is unfailingly courteous, adhering to the chivalric code of conduct in his interactions with others.

Piety: His devotion to God and the Christian faith, highlighting his religious convictions.

The interlocking and continuous nature of the pentangle symbolizes the interconnectedness of these virtues in Gawain's character. The pentangle serves as a moral compass, guiding Gawain in his quest for virtuous behavior. Each of these virtues are tested during his quest to face the Green Knight and receive his blow.

However, the pentangle is not only symbolic of virtues. It also symbolizes the faith Gawain carries with him. Each point of the pentangle represents one of the five wounds of Christ (hands, feet, side) as well as the five joys of Mary (annunciation, visitation, nativity, presentation of Jesus at the temple, and the assumption into heaven). Though the pentangle/pentagram is often assumed to be a pagan symbol, it actually has deep roots within Christianity—as attested by this story.

The 20th-century theologian, Valentin Tomberg, articulated the Christian understanding of the pentagram quite well:

With respect to the third form of magic—sacred magic—the method it makes use of is not the force of the will, but rather its purity. But as the will as such is never entirely pure—for it is not the flesh which bears the stigmata of original sin, nor thoughts as such, but rather the will—it is necessary that the five dark currents inherent in the human will (i.e., the desire to be great, to take, to keep, to advance and to hold on to at the expense of others) are paralyzed or “nailed.” The five wounds are therefore the five vacuities which result in the five currents of the will. And these vacuities are filled by will from above, i.e., by absolutely pure will. This is the principle of magic of the pentagram of five wounds. (Tomberg, Meditations on the Tarot, 109-110)

For Tomberg, the pentagram represents how spiritual symbols can transform the soul. This transformation aligns with St. Paul's words in Galatians 2:20: "I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me; and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave Himself up for me" (NASB). This transformation is manifest in the sacred magic (theurgy) of Christian liturgical life that participates in the transformation of all Creation through reconciliation with God in Christ (cf. Colossians 1). Through these practices, one participates in the faith's symbolic structures, which serve as a gateway and guide into the heavenly world. The sacraments manifest invisible grace, icons reveal spiritual reality, and the sign of the cross bestows divine blessing. These ritual practices unite art and life, bridging logical and intuitive understanding, just as the pentangle is a sign of integration.

This pentagram-centered integration manifesting as theurgy in the sacraments and sacramentals of the church is shown quite powerfully in the scene from the poem when Gawain is lost in the wilderness at the beginning of his quest. In this scene, Gawain, lost and weary, prays fervently to Mary and makes the sign of the cross five times in remembrance of Christ's wounds. After this liturgical act, he discovers Bertilak's castle, suggesting that his participation in these sacred prayers opened a path forward in his quest. This moment beautifully illustrates how the symbolic power of the pentagram, when enacted through liturgical practice, can transform seemingly hopeless situations into opportunities for grace.

Through these liturgical practices, which embody the divine theurgy of the pentagram, those who suffer can find a connection with Christ's own wounds. Facing one's suffering, trauma, and death is an incredibly difficult endeavor, requiring ample amounts of courage, divine strength, and communal support. But those who undertake such a journey, like Gawain wandering through the wilderness on his quest, feeling hopeless, desperate, and lost—do not travel empty-handed. Participation in the liturgical life cultivates an awareness of and participation in the movement of the Holy Spirit, who bestows upon us the armor of God. In this sense, we are all the Knight of Pentacles, the knight in the tarot card game, who carried a pentagram/pentangle in his hand.

Tarot is originally a card game, similar to the Western adjacent games. Like in poker cards, tarot has different suits, which have different symbolic meanings associated with them. (Note: these symbolic systems are which are not necessarily divinatory in nature, and there are some Jungian schools of thought that engage with tarot as a system of archetypes for personal reflection and not as divinations). The suit of pentacles is symbolically associated with the material realm and the life of the everyday. The Knight of Pentacles is a representation of diligence, grit, persistence, hard work, and seeing things to completion even when they take some time. He is seated upon a workhorse rather than a war horse, and they stand in the middle of a farmer’s field instead of a battle. The plowed fields in the background symbolize hard work, preparation, and cultivation. They imply that success comes from persistence and effort over time.

One can see Sir Gawain as resembling this archetype. Yet, the Green Knight offers a dialectical counterpart to this image. While Gawain, through his prayers and adherence to the chivalric and liturgical codes, embodies the diligence and material preparation of the Knight of Pentacles, the Green Knight represents a wild, uncanny force that transcends mere materiality. He is natural (connected to nature) in a profoundly supernatural way, embodying the liminal space between life and death, chaos and order. As a figure of the wilderness and the supernatural, he forces Gawain to confront not only external trials but the deeper, unresolved tensions within himself.

Repression of the Non-human

The Green Knight bears striking similarities to the Celtic Green Man, a mythological figure representing the cycle of growth and rebirth in nature. Like the Green Man, whose face is often depicted as being made of or surrounded by foliage in medieval church architecture, the Green Knight's green complexion and supernatural vitality connect him to vegetation and the natural world. Both figures embody the wild, untamed aspects of nature and its regenerative powers— the Green Knight's ability to survive beheading mirrors the seasonal death and rebirth cycle that the Green Man represents.

Furthermore, both figures serve as bridges between the civilized and natural worlds. Just as the Green Man appears in ecclesiastical architecture as a reminder of humanity's connection to nature, the Green Knight enters Arthur's courtly world from the wilderness, challenging the artificial boundaries between civilization and the natural realm. His role as both a knight and a supernatural creature of nature echoes the Green Man's dual nature as both a wild force and a figure incorporated into Christian imagery. Gawain must discover this incorporation for himself.

These themes situate the character of the Green Knight within the long tradition of ghost stories at Christmas. Spanning back into even pre-Christian Europe, Christmas and Winter Solstice have been thought of as a time in which, like Halloween, the veil between the natural and spiritual worlds is thinnest. Ghost stories were thus a common feature of Christmas celebrations for many generations. As a paranormal, quasi-spiritual entity, the Green Knight inhabits that liminality of the spiritual breaking into our world at Christmas.

However, as JF Martel described in a lecture for his “’Tis the Season to be Ghostly” event this year, “the ghost is the inhuman aspect of the human.” As I understood him, I don’t think this is merely inhuman in the sense of cruelty (though such an interpretation makes sense), but also includes inhuman in the sense of non-human. This insight is seen quite powerfully in the dichotomy of the Green Knight and Gawain: the Knight is the inhuman (non-human) aspect of Gawain—the interconnection each individual holds to all Creation. As the ghost of the Green Man, he represents and reminds us that mind is “everywhere already” (Martel). This is not to collapse into a crude pantheism. Rather, it is to express, along with scripture and various traditions in Christianity, that God is the animating force of the cosmos. As a sophiologist myself, I believe that the Wisdom of God (Sophia) is the ontological foundation of Creation—the World Soul, implanting the sophianic seeds of being in reality, from which we and the rest of Creation spring. Much of Christian tradition has devolved into an unwarranted belief that God only loves or cares about humans—or that humans are in some sense the only things truly ‘alive.’ However, this is far from the case. As scripture teaches, “For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross” (Col. 1:19-20 NRSVUE). The reconciliation and divine healing is working “as far as the curse is found” (to quote “Joy to the World”)—in all aspects of Creation that groans in anticipation for its redemption (Rom. 8). The same God who animates and gives life to all Creation is simultaneously working in both the human and non-human aspects of Creation, to bring all into reconciliation.

This theological understanding of God's universal reconciliation helps explain the Green Knight's role as a ghost figure. As a supernatural entity appearing at Christmas, he represents the "inhuman aspect of the human" by reminding us that we are not separate from, but deeply connected to, all of Creation. He is the ghostly haunting of that which Christianity often represses—the vitality of Creation beyond the human. His ghostly presence reveals that the divine animation of life extends beyond human consciousness into every aspect of the natural world. Like all ghost stories, his appearance disrupts our normal categories of understanding, forcing us to confront the reality that the human and non-human, the natural and supernatural, are more intertwined than we typically acknowledge.

The Green Knight's dual nature as both an anthropomorphic figure and a supernatural force of nature embodies this theological truth. He shows Gawain (and us) that the inhuman aspects we try to separate ourselves from are actually integral to our full humanity. His ghostly manifestation at Christmas thus serves as a reminder that God's reconciling work encompasses not just human salvation, but the redemption of all Creation, including those wild and uncanny elements we often try to suppress or deny.

On Trauma

As JF Martel and Phil Ford described in the aforementioned event, ghosts represent the real behind the imaginary, a type of revelatory perception in a deeper aspect of reality. It is an encounter with something that doesn't fit into our matter-spirit binary, but is rather "psychoid" as Carl Jung described—a type of intermediary reality that exists between the physical and spiritual realms.

This psychoid aspect of the Green Knight represents a kind of living symbol that transcends our usual categories. In this respect, it is hard for me to read the story and not think about themes of trauma. Though the text is not explicitly addressing trauma as such, it seems to me that Gawain’s journey parallels much of post-traumatic recovery. The integration of the wild and the civilized, the supernatural and the natural, parallels the journey of trauma recovery. Just as the Green Man is incorporated into Christian architecture—maintaining his wild vitality while being transformed into something new—trauma survivors must find ways to integrate their experiences without completely taming or denying them. The process isn't about eliminating the wild or frightening aspects of our experiences, but rather about finding ways to incorporate them into a larger, more complete sense of self.

Like the Green Man motif appearing in sacred spaces, our wounds and traumas can become portals to deeper understanding when properly integrated. They remain part of us, like the green foliage forever part of the Green Man's face, but they can be transformed from purely destructive forces into sources of wisdom and growth. This integration doesn't diminish the reality of the trauma, just as the Green Man's incorporation into Christian imagery doesn't deny his wild nature. Instead, it creates a new wholeness that honors both the civilized and wild aspects of our experience.

Much like how trauma itself often defies our normal frameworks of understanding, the Green Knight’s appearance as both natural and supernatural, both living and undead, captures something of the ineffable quality of profound psychological and spiritual experiences that exist at the threshold between ordinary reality and the numinous, which take on a horrific and unsettlingly dark tone in trauma.

The Green Knight’s greenness, a color associated with life, growth, and renewal, also carries the connotation of decay and mortality. His challenge—the beheading game—is at once a confrontation with death and an invitation to transformation. By engaging with the Green Knight, Gawain embarks on a journey of integration, where he must reconcile the cultivated order of the pentagram with the untamed vitality and mystery of the Green Knight. In this sense, the Green Knight is a mirror for Gawain’s inner struggles and a catalyst for his growth.

This dialectic has profound connections to the themes of trauma. Trauma often leaves one feeling severed, as though wandering in the wilderness of one’s own mind. The Green Knight’s challenge—a confrontation with mortality and the uncanny—reflects the disorientation and fragmentation that accompany such experiences. Like Gawain, those who have suffered must face the wilderness within, engaging with forces that seem both natural and supernatural in their intensity and disruption. Through this confrontation, a path toward integration and renewal becomes possible.

The interplay of the Green Knight’s uncanniness and Gawain’s persistence as the Knight of Pentacles suggests that true healing and growth require both the diligent effort of cultivation and the courage to face the unknown. The Green Knight, as a symbol of the uncanny natural-supernatural, invites us to embrace the complexity of trauma—its disorienting and transformative potential—and to find within it the seeds of renewal. Like Gawain, we must learn to integrate the wildness of the Green Knight with the cultivated strength of the pentagram, finding grace and strength in the dialectic between the two.

On Virtue

The themes of virtue in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight are intricately woven into this dialectic between order and chaos, cultivation and wilderness. Virtue, as represented by the pentangle, is not merely a static set of rules or ideals to be rigidly followed. Rather, it emerges through the dynamic interaction between our aspirations for moral excellence and our confrontations with our own limitations and the uncanny aspects of existence.

Just as Gawain must face the Green Knight to truly understand and embody the virtues he claims to represent, authentic virtue often requires us to confront that which seems to threaten or challenge our moral certainties. The journey toward virtue is not a straight path of perfect adherence to ideals, but rather a complex process of integration that includes our failures, our fears, and our encounters with the unknown.

This understanding transforms how we view virtue itself. Instead of seeing virtues as fixed qualities to be achieved and maintained, they become dynamic capacities that grow through challenge and even apparent defeat. In other words, they rest upon the deification and sanctification that comes through God’s grace. The Green Knight's role in testing Gawain's virtues ultimately strengthens them by revealing their true nature—not as perfect achievements but as ongoing processes of growth and integration.

However, as the story continues, we also see that even Gawain, the most chivalrous and virtuous of all knights—the epitome of the Knight of Pentacles—is unable to be truly perfect. Before departing to face his potential beheading, he lies about receiving a magic protective sash, refusing to exchange his gift with the host as per their earlier agreement. The threat of one’s mortality can often call one’s honor-bound oaths into question. These moments happen to us all. Though no one can fault Gawain for such an action (I’m sure I would do the same thing), it’s still a sign that he too is prone to imperfection.

But here’s the main point: The author of the text is deeply critiquing the insistence upon a perfect piety that was rampant during his time. He is writing not too far before the Protestant Reformation. The caricature of this period is that every single Catholic thought that you had to be perfect and buy indulgences until Luther was the first person since Paul to ever think of grace. But of course, many different ‘reformations’ were happening throughout the time, including many within the Catholic church itself, which were inviting a deeper emphasis on grace. The author of this poem fits perfectly into this milieu. Gawain shows us that no one can be perfect in their piety. Everyone will cave to sin, even when it is born from fear and not malice. But importantly, the author insists that such an embrace of grace leads to something even more beautiful than our piety alone, great as piety might be.

The author communicates this theme by placing the two pivotal moments of the story—the two beheading scenes—on the liturgical day of Christ’s circumcision. I am aware that topics of circumcision can be quite awkward, but I promise to be mature about it because the theology behind Christ’s circumcision, and its relationship to Sir Gawain, is very important. For the early church fathers and throughout much of Christian history, the circumcision of Christ was viewed with great reverence and awe. Christ’s flesh being cut in circumcision is the first time in which his blood is shed for the sake of redeeming Creation. As Cyril of Alexandria says,

But recently we saw the Emmanuel lying as a babe in the manger, and wrapped in human fashion in swaddling bands, but extolled as God in hymns by the host of the holy angels. For they proclaimed to the shepherds His birth, God the Father having granted to the inhabitants of heaven as a special privilege to be the first to preach Him. And today too we have seen Him obedient to the laws of Moses, or rather we have seen Him Who as God is the Legislator, subject to His own decrees. And the reason of this the most wise Paul teaches us, saying, "When we were babes we were enslaved under the elements of the world; but when the fullness of time came, God sent forth His Son, born of a woman, born under the law, to redeem them that were under the law." Christ therefore ransomed from the curse of the law those who being subject to it, had been unable to keep its enactments. And in what way did He ransom them? By fulfilling it. And to put it in another way: in order that He might expiate the guilt of Adam's transgression, He showed Himself obedient and submissive in every respect to God the Father in our stead, for it is written, "That as through the disobedience of the One man, the many were made sinners, so also through the obedience of the One, the many shall be made righteous.] He yielded therefore His neck to the law in company with us, because the plan of salvation so required: for it became Him to fulfill all righteousness.

Additionally, it is at this moment where the Messiah is officially christened with his name: Jesus, the name above all names. This moment is especially foundational for the Orthodox Church, which holds the Jesus Prayer (”Lord Jesus, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner”) to be the pillar of the church’s faith proclamation and devotion. This holiest of moments is brought simultaneously in bodily wounding, and perhaps one could even say bodily trauma—especially given the typological link between the circumcision and the crucifixion.

Importantly, as it relates to Sir Gawain, the feast of the circumcision of Christ, the eighth day after Christmas in the liturgical calendar for the author’s era, is the day on which the two beheading scenes take place (at the party in the first act and at the Green Knight’s chapel in the last act). The author is symbolically linking the beheading to the circumcision of Christ, conjuring up themes of facing suffering on the way to redemption. But importantly, the setting of this feast day reminds us of one of the other major teachings of this feast day: Christ’s fulfillment of the law. Because of Christ, the shedding of blood is replaced with baptism—a sacrament of pure grace that is received from the community (in many traditions, as a baby) and not earned through piety. This is not to minimize piety, for as Jesus says in Matthew 5:7, “I did not come to abolish the law, but to fulfill it”). Rather, piety is brought to its completion in Jesus.

This truth is powerfully illustrated in Sir Gawain's journey, where his adherence to chivalric codes and pious practices, while valuable, ultimately proves insufficient on its own. His story demonstrates how grace operates not as a reward for perfect devotion, but as a transformative gift that meets us in our imperfection.

The truth of the matter is that, despite the importance of pious devotion, no amount of discipline can truly save us. Redemption is an act of God as a gracious gift to all creation, not as an economic exchange with a few individuals. This is not only true in terms of eschatological redemption but also regarding other situations in life. PTSD is not healed through having a little bit more self-discipline. Self-discipline, piety, and devotion can certainly help manage symptoms, but they will often not get at deep inner healing on their own.

In his moment of desperation in the wilderness, when all his training and virtue seem insufficient, Gawain encounters refuge through the grace-filled manifestation of the castle. This mirrors the Christian understanding that our deepest healing often comes not through our own strength, but through a divine intervention that meets us in our weakness. Just as Gawain's desperate prayers lead to unexpected salvation, those wrestling with trauma may find that their breakthrough moments come not from perfect adherence to therapeutic techniques, but through moments of sublime grace and in communities of love. This is not to minimize therapeutic techniques any more than it is to shun faithful devotion. But it is rather to highlight that healing has a transcendent source that cannot be reduced to systems of technique alone. Our techniques are bound to fail or be incomplete. But when they are placed in proper relation to the transcendent, when we acknowledge our absolute dependence upon the Infinite, our techniques can be made into something even more beautiful.

Gawain’s transformation at the end shows that chivalry and piety—when marked by a received grace and integrated through humility—become something even more beautiful than before. Even the most perfect knight in the realm cannot achieve salvation through works alone. This truth is made manifest in Gawain's journey, where his greatest moment of grace comes not through perfect adherence to the chivalric code, but through his confrontation with his own limitations and failures. The Green Knight's mercy—like divine grace itself—transforms Gawain's shame into a deeper understanding of virtue, one that encompasses both human frailty and divine forgiveness.

The structure of the poem itself illustrates these themes and shows what a creative genius the author is. Back in this era, a 'perfect' poem would consist of 100 stanzas. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight contains 101. This extra stanza serves as a beautiful metaphor for the poem's message about grace transcending perfection. Just as Gawain's journey reveals that true virtue lies beyond mere perfect adherence to codes, the poem's structure itself demonstrates that beauty can exceed conventional standards of perfection. The additional stanza stands as a testament to how grace operates beyond our human systems of measurement and achievement.